As a child, there was always a particular thrill when winter truly settled onto the landscape. Suddenly I’d feel a chill when running outside. It would be time for gumboots and raincoats. I remember the sound of frogs, and the little creek down the back paddock coming to life again. I also remember the sharp taste of sourgrass, and the lemony smell when I would snap a stem to munch on. My siblings and I could pick a snack of sourgrass wherever we were adventuring, whenever we wanted, because it grew so rampantly.

Sourgrass doesn’t often go to seed in Australia. Instead it spreads by bulbs underground. Not long after the first rains, the bulbs that have been hiding from the summer heat stir in the soil, sending out bright masses of green.

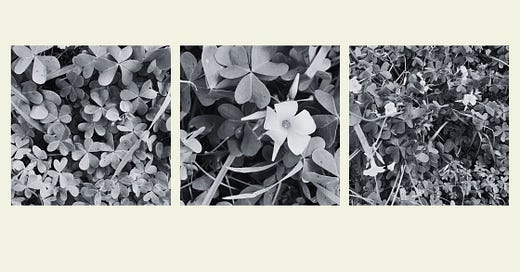

The leaves resemble clovers: three little heart shapes arranged in a circle at the top of a crunchy stem. Later, the sourgrass puts out flowers, their bright golden petals announcing their lemony taste loud and clear.

As I grew older, I became aware of the negative response sourgrass could elicit. What was a sensory delight for me as a child was often a source of deep sighs in adults, especially those who tried to keep a neat garden. Plants that grow persistently in unwanted places often become objects of frustration. We may even begin a hierarchy of plants in our minds: ones that are ‘real plants’ and ones that are too common to be beautiful.

Sourgrass, the affectionate name we used as children, is scientifically called Oxalis pes-caprae L. and is native to South Africa. It’s so invasive and persistent that it’s now found the world over, which is probably why it has so many names: Soursob, Bermuda Buttercup, Cape Cowslip, Yellow Sorrel, Geelsuring…

In rental houses I’ve spent many hours pulling sourgrass out of the soil to maintain the illusion of tidiness, but to be honest, I don’t mind the green masses of it, especially if it’s growing on empty patches of ground or brightening the margins between fence and footpath. Sourgrass reminds me of childhood, of freedom and exploration. It still gives me a heady thrill when, after such a brown and dry summer, it begins brightening the city-scape.

I’ll still pull them out of garden beds and pots if I want to give other plants a fighting chance, but I’m not offended by their persistent presence. And while I might not be munching on their juicy stems for a snack anymore, I will from time to time gather a handful of leaves and add them to a salad. You can also chop the leaves finely, let them sit in a glass of water for five to ten minutes, and then strain for a tangy tonic.

According to The Weed Forager’s Handbook, oxalis species are rich in vitamin C and some have powerful antioxidant properties. They are high in oxalic acid, so they shouldn't be eaten in large mounds (but who could stomach all that sourness anyway?) and if you’re pregnant, please avoid as oxalis species can prevent fertility in women.

It’s the plant from my childhood that I still see most commonly around where I live, but there are many species of oxalis that grow in Australia. Particularly pleasing are the purple-flowering species. Without flowers, you might mistake clover for oxalis, as they have the same heart shaped leaves. They’re both edible though, so no need to worry. A simple pop in your mouth will tell you which one you’ve found: oxalis will shock you every time with its sharp, acidic flavour.

Sourgrass in the kitchen

Add young, healthy leaves to a salad, such as this potato and egg salad

Garnish your plate with the flowers

Cook a quick and simple pasta with olive oil, sourgrass and parmesan

Include in hot dishes like risottos and casseroles

Toss the leaves and flowers into a fruit salad

Use as a lemon substitute, in a pinch!

Soak leaves in water, drink as a vitamin C-rich tonic (sweeten with honey if you desire)

We tended to have more of the white or purply pink flowers on our oxalis in NZ. One day, during my school years, I helped weed an elderly neighbours garden. She gave me some vege plants to take home and, to the dismay of my mother, I inadvertently introduced oxalis bulbs into our own garden where they flourished. To pull them out I remember having to loosen the soil underneath and carefully lift the plant so none of the dozen or so bulbs, precariously holding onto each other, would fall back to the ground and restart the cycle. I notice a few yellow flowered oxalis emerging in the lawn here. Will have to try some of those culinary suggestions. Thanks again for your thoughts and ideas.

So fascinating and lovely to read 🌿 I didn’t know so much of this!